Folklore is defined as ‘the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through the generations by word of mouth’ or ‘a body of popular myths or beliefs relating to a particular place, activity, or group of people’.

Folkore encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. These include oral traditions such as tales, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging from traditional building styles to handmade toys common to the group. Just as essential as the form, folklore also encompasses the transmission of these artefacts from one region to another or from one generation to the next. For folklore is not taught in a formal school curriculum or studied in the fine arts. Instead these traditions are passed along informally from one individual to another either through verbal instruction or demonstration.

Folk refers to ‘people’ whilst ‘lore’ comes from Old English lār ‘instruction,’ and with German and Dutch cognates, it is the knowledge and traditions of a particular group, frequently passed along by word of mouth.

Transmission is a vital part of the folklore process. Without communicating these beliefs and customs within the group over space and time, they would become cultural shards relegated to cultural archaeologists. For folklore is also a verb. These folk artifacts continue to be passed along informally, as a rule anonymously and always in multiple variants. The folk group is not individualistic, it is community-based and nurtures its lore in community.

Folklore as a field of study further developed among 19th century European scholars who were contrasting tradition with the newly developing modernity. Its focus was the oral folklore of the rural peasant populations, which were considered as residue and survivals of the past that continued to exist within the lower strata of society. The “Kinder- und Hausmärchen” of the Brothers Grimm (first published 1812) is the best known but by no means only collection of verbal folklore of the European peasantry of that time. This interest in stories, sayings and songs continued throughout the 19th century and aligned the fledgling discipline of fol-kloristics with literature and mythology. By the turn into the 20th century the number and sophistication of folklore studies and folklorists had grown both in Europe and North America. Whereas European folklorists remained focused on the oral folklore of the homogenous peasant populations in their regions, the American folklorists, led by Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, chose to consider Native American cultures in their research, and included the totality of their customs and beliefs as folklore. This distinction aligned American folkloristics with cultural anthropology and ethnology, using the same techniques of data collection in their field research. This divided alliance of folkloristics between the humanities in Europe and the social sciences in America offers a wealth of theoretical vantage points and research tools to the field of folkloristics as a whole, even as it continues to be a point of discussion within the field itself.

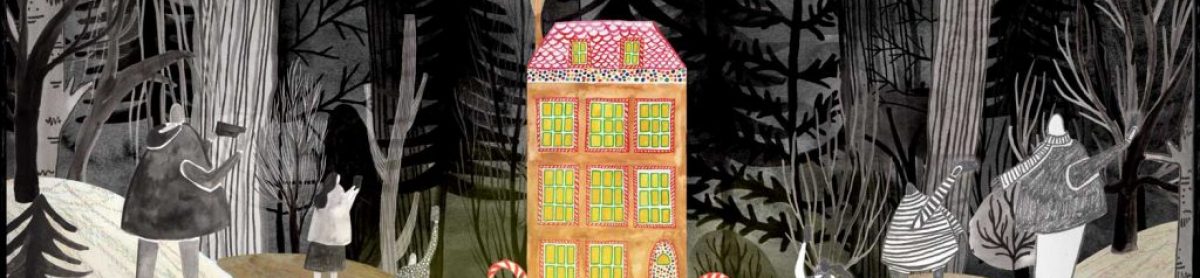

Folklore consists of music, narratives, art, sayings, child games, traditions, ceremonies, building styles and handmade toys. Their are many different types of narrative folklore such as folktales (oral tales reflecting values and customs), animal tales, fables (a subgenre of folktales that use anthropomorphic animals to illustrate a moral), fairy tales (involving magical, fantastic characters and events etc), tall tales (stories about a real people whose exploits are wildly exaggerated), myths (featuring deities) and legends (set in the past and tell of heroes and kings). A folk narrative can have both a moral and psychological aspect, as well as entertainment value, depending upon the nature of the teller, the style of the telling, the ages of the audience members, and the overall context of the performance.